Shareware Heroes

ISBN:978-1800181748

ISBN:978-1800181748

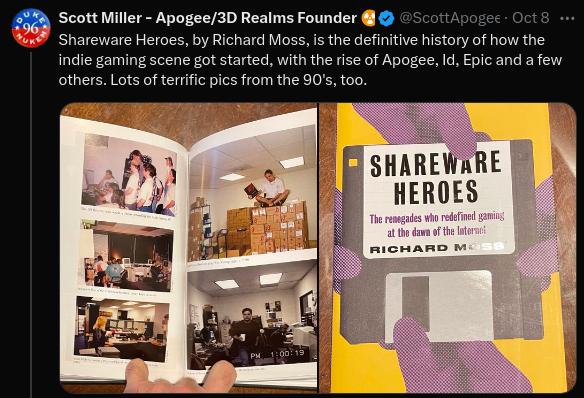

Scott Miller was a guy at the right place at the right time for the Shareware time period. His Twitter account happened to post something about a new book about the Shareware Era of gaming:

Not long after that, bookshop.org featured an anti-Amazon free shipment on books day, and happened to have Shareware Heroes as a featured book. “Fine,” says thebooklight reviewer. “The reviewing shall commence.”

This is not a book that probably just anyone from any period can pick up and enjoy. There are many moments of “you kinda had to be on that scene” to really understand why a given moment was exciting. There are many developments in modern gaming that we take for granted. Something that has been relegated to the wayside, however, is the kind of distribution Shareware had originally. The condensed version of this model was simply that it was possible for a lone programmer to pump something out and have his or her work distributed to people who might be willing to support future work. All that was necessary was to ask for a donation if someone enjoyed the game or utility. Usually, the amount asked for was around $10. The way the software was distributed was through BBS’s or Bulletin Board Systems which were sites people with phone lines and modems and sometimes though rarely T1 or T3 lines could host from their home if they wished. One could argue that in many ways, this was a less centralized time other than having the money for the hardware which was the bigger limiting factor.

Originally, as the book discusses, the entire game was given away for free while the aforementioned $10 was asked if someone enjoyed the game. These models were refined by companies like Miller’s Apogee, or another biggie, Id. All of these companies were trying to find the right level of giving things away for free versus reaching new customers who wanted to pay for the innovation. The result, of course, famously produced two huge titles which feature, perhaps not surprisingly, Nazis, and Demons from Hell, in that order. “Wolfenstein”, and “Doom” is another way of designating those titles. Turned another way, it was a little like the gaming hits of that era were memories of WWII being presented at a certain kind of angle. Maybe it was similar to a gaming purgatory where the games were a place to work out some stuff not entirely possible in reality. The quote “War is Hell,” though, were visibly borne out in the creation of the titles. Lest you think this is fanciful, let us also recall another huge title roughly in that sequence called “Duke Nuke’Em.”

Shareware Heroes does a great job of filling in a million little blanks that probably a casual reader did not even know existed. ID studios, for example, was an acronym at first. The book tells you what it stood for. Apogee, at a certain point, needed a new gaming engine. The surprising answer to where it was found and how it was made and what happened is in the book.

It might be better to say this book as at its best when it tells the story of Apogee and Id. It uses a format where it flashes to other game designers, but the timeline continuity of the narrative format suffers somewhat for this approach. The reader has to “remember back to that chapter on Apogee” which breaks the momentum. It does allow for telling the story of some other interesting characters, however, like Dave Snyder and his company MVP which is probably no longer a common thing to know about.

There are also screen captures from the games, and plenty of 90’s style pictures of the developers in the middle of peak geekdom. These definitely add flavor and a sense of humanity to the otherwise long churn of business models along with hits and misses that are occupying the bulk of the work.

What one cannot escape, however, is the sense that one is reading a eulogy of something that was and not something that still is or is going to be. Indeed, the last story concerning the game “Tread Marks” about a certain tank game developer is the epitome of moribund reminiscing. The story is certainly relevant–but it is also morose which one wonders if somehow all the gaming began to take a wrong turn at this juncture.

One tale about a game called “Escape Velocity” might be a kind of indicator as to why things shifted. Originally, gaming was the exception. Computers were a new thing, and if you had an hour or two as a kid between everything else going on in your life, you’d play. The maker of the game “Escape Velocity” picked up a copy of “Elite” when he was ten, but he lost the key to the copyright protection and so he could not play it. Instead, he had to imagine how awesome the game was, and “Escape Velocity” was his answer to those imaginings. In other words, it is great to imagine something, but then there is also the work of doing something to bring the imagined thing here. This is what is termed “art” and the wide variety of the early history of gaming has plenty of art. Later, that art starts turning more into crack. No longer was it about dealing with stuff or coming up with newer game mechanics but instead the desire is to “hook” the gamer on gameplay or escapism. Since the games were originally given away for free, the total escapism ability was low in the early days. Now everything is rigged for it. Even back then, though, there is at least one story of a developer who put everything on the line for his dream and lost his house and his sanity trying to sell and market a game–another interesting story in the book.

So what’s the verdict? Shareware Hereos is a great read if you are willing to admit that the days of the shareware publishing are essentially over and are now rolled into “freemiums” and “indy” types of scenarios. Shareware was indy, but it was also a little cooler than that. You could shove your code or your work up, never talk to a living soul directly, and make enough money to buy a house or raise a family. I’m not sure “Indy” has that same meaning, or “freemiums”. While the 90’s had a lot of problems, there was an aura of optimism around the ability to share and publish information that is now missing. This reviewer does not accept a euologized version of that era as the final word. Instead, the counsel is direct–rage, rage against the dying of the publishing model light! Do not go gently into that good night. Buttress your open sources, and fly high the flag of free press and distribution!