ISBN:9781770894303

ISBN:9781770894303

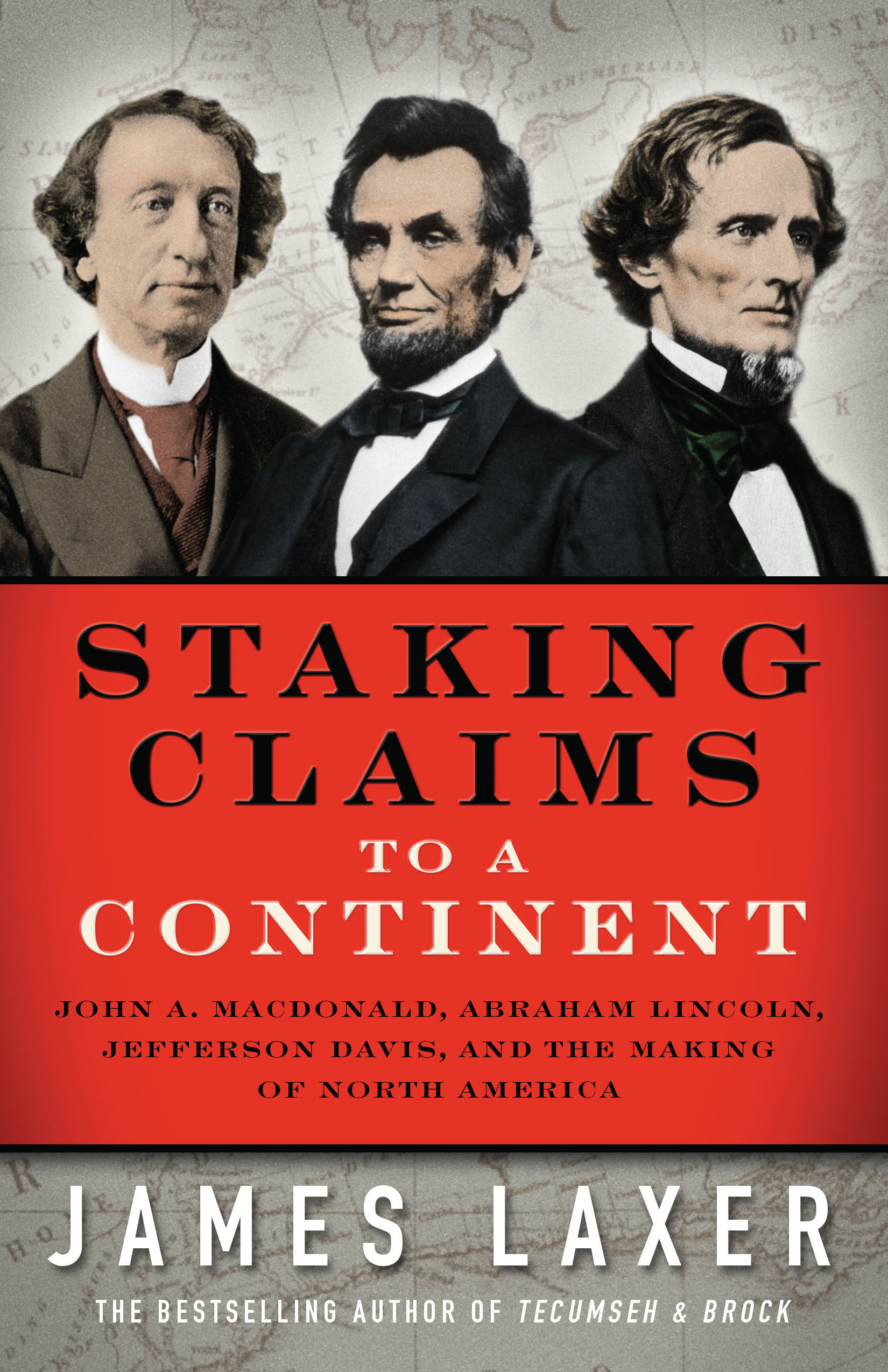

James Laxer undertakes a difficult task in 352 pages. His objective is to tell the reader how the North American continent was sliced and diced among the predominant powers of the 19th century. The picture on the cover indicates the method by which this feat will be advanced—through the lives and political careers of three men—Jefferson Davis, Abraham Lincoln and John A. Macdonald.

Lincoln and Davis feature more as an impetus to discuss how Canada, and consequently, John A. Macdonald, a Canadian politician who rose to the top of the game before there was a Canada to have a political game, viewed events. Specifically, the events that most concerned Canada were how to protect its boarders and how to assert political boundaries that were governable. Macdonald is thrust about on this sea where the debate centers on representation by populist means, confederated means, and federated means. Since Canada is composed of many differing kinds of people at this time and they all have their own identities and who they believe themselves to be, Macdonald is tasked with convincing them otherwise. He does this, mostly, by assuming that Britain is a superior power and that the right to govern others naturally belongs to him and the crown. He likewise notices the U.S. Constitution is a mess because it is decentralized among the states. In that observation he is not alone, and Canada decides to adopt a kind of government with a stronger federalization emphasis because of this example. Not a little of these considerations are brought about because Canada can see that the United States is very eager to manifest their land destiny across the borders of what would not be considered to be US territory. Because the Civil War all ready has the military organized and ready to roll, Canada feels that the time is ripe to start becoming a nation or else miss the boat entirely. If this happens, then the supposition is that large parts of Canada will become US states.

Macdonald is easily the most interesting subject in the book in part because so many other books about Lincoln and Davis have been written. As he grapples with how to advance the political will of a United Canada, he, like those who are commonly written about in the US, silences native populations and disregards their rights and ancestral land claims.

Laxer is also reminding us as the work unfolds that the South in the US considers itself to be a separate people from the North. This identity is what foments the conditions around the Civil War along with attitudes toward slavery ranging from being a necessary evil to a greater good. This is in contrast to the Northern US who have become more industrial, less agrarian, and who, it is noted, have to stay inside during winter. So, the South through cultural identity makes a land grab, the North through cultural identity disallows this while also making additional land grabs, and Canada sets out to make land grabs before the US gets around to making them instead.

As Lincoln has been written about so often, it was easy to spot some scholarly assertions about his life in the narrative that are not widely agreed upon or are else told differently elsewhere. Laxer does not necessarily tell the reader, however, where all his facts are sourced on certain claims so it is hard to know whether Laxer realizes there is disagreement on a subject or else has made up his mind and decided his account is the correct one. Most of these kinds of facts are easy to spot for people who are familiar with American scholarship, but it does make one wonder if the same kind of latitude was assumed with Macdonald. Whether or not this is so, the exposition concerning Macdonald is interesting enough to not make the read irritating. If Laxer is not telling us the full truth, he is at least doing it in a way that makes the journey pleasant.

There are parts, however, that become more tedious, and the end of the work feels rushed where Macdonald’s story is concerned. This is due, in part, to the sub-plot of Louis Riel who is hanged because he resists, on behalf of the resident Métis populations, Macdonald’s political “improvements”. These improvements concern not recognizing existing claims that the Métis people have along with their right to self-govern.

The end of the Jefferson Davis/Lincoln dialog stops with Lincoln’s assassination and reconstruction falling apart. The “Lost Cause” new identity/mythos/quasi-religion is then parsed in the context of the “new identity” of the South where it continues to wage war by means of propaganda instead of rifles. This is a logical place for this narrative to conclude although we do get a few pull-quotes later about how Jefferson Davis is not penitent in 1861 for his actions and how his later life seems to keep underlining that stated point.

The short summary of the entire body of the work could be stated as “identity politics when nobody knows their identity”, or else they know their identity and the politics are not matching. We find the solution to this quandary varies, in terms of political arrangements, but the constant is “some people are gonna lose their rights and culture in this process because we are better than them”. Whether that “better” is because of prosperity, freedom, state’s rights, or a federated parliamentary government under a monarchy seems to matter little. The only thing to be negotiated is how much blood these ends are going to require and who gets the bill. For this reason, Laxer’s book is worth the sticker price.

ISBN: 978-1636415208

ISBN: 978-1636415208

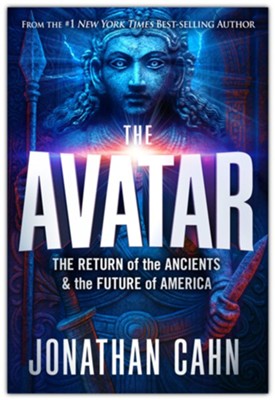

As a reader of thebooklight will know, Jonathan Cahn, a Messianic congregation leader, has written many books. Several of his works have been reviewed by the same. His latest work is called The Avatar and seeks to explain how the patterns which he has noted in some of his previous work have expanded. Specifically, he endeavors to explain how the lives of many pagan gods have patterns which have been appearing on the stage throughout his life. For this, he offers some testimony about his experiences in India, Cuba, and Africa that he has not previously disclosed in his former works. The narrative is shaped, then, by what “the gods” have been doing on the national stage for the past sixty or so years and Cahn has specific testimony in his experiences to add the flavoring of what this means practically speaking.

The parts concerning Cahn’s testimony and experiences in India and Cuba and Africa are fascinating. A short synopsis of this content would be “Things got wild”, in the sense that literal demons are involved doing demonic activities that Cahn and his entourage must battle.

Then, by about mid-book, we switch into an analysis mode of who the “gods” are, and who they correlate to. This is after we discover who they are typifying in the Bible, which, it turns out, is one mask they are wearing. Some of these people, like Trump, are not featured with a pagan mask–probably because Trump appears to be motivated by the Bible in his actions although not necessarily perfectly. It turns out there is a Biblical example for another person who did this very thing, and Cahn does an excellent job of noting the parallels.

Where Cahn loses the script, perhaps, is that he goes on about the pagan gods for most of the middle of the book. This, plus the fact that he relies on time measurement that is Babylonian and Roman to correlate certain events happening make it seem more like he is in alignment with the Roman Emperor than with God. It’s not, of course, that the Torah readings across the world cannot be used to understand something of events unfolding, but one could ask the question why those specific verses are read. Who decided it? Same thing with the calendar for events. We know Rome decided that the Roman calendar had to be instituted.

In fairness, most of Cahn’s readership is probably Roman Christians who identify as Messianic. There is a good chance he knows this and so has to use this kind of writing style to move books since his readership likely will not respond to much else. Fine. A writer has to write in a way that sells books if he wants to have his message spread. What is confusing, though, is why Cahn feels the need to spend so much time on the pagan god templates? His readers probably are not familiar with these entities, so by saying their name so frequently, is he not causing his readers to think about the very gods he is warring against? It seems like this work loses focus in this regard. Yes, there are pagan gods. Yes, on the national stage they have been named. Yes, their worship does thus and so, but who cares what they are doing in certain specific ways? Their end is always the same. Sooner or later, the idols are destroyed. Cahn makes this point, but it is not as solid of a thesis as one might hope for from the work. The ending quickly touches on it, and tells us we should pray and America is at a spiritual crossroads. Fine. Which name does America need to hear more of, then? YHVH? The Hindu pantheon of gods? It is an odd move. Perhaps Cahn felt like he had to prove his case, and so felt compelled to show his work. Maybe he has another book in mind.

Whatever the case, Cahn suggests America is in some twilight between these ancient gods and the Bible and that it hangs in the balance. One could make the same critique of this book. The scholarship is excellent. The connections are solid. The testimony is phenomenal and one yearns to hear more of what God did in Cahn’s ministerial adventures. One, however, gets to hear instead about much evil for entities one ought not be serving as a Messianic while using a calendar that was instituted, in no small way, to punish early Christians. This makes this a peculiar work, although given the body of Cahn’s other books, one can forbear final judgment on this piece until more time has elapsed. Cahn introduced us to the pagan gods. What is he going to do about that, now? Tell us to pray? Okay. Were not people doing that before this book emerged?

Cahn shows us the battlefield and the war, but leaves us with little idea concerning actionable steps to take. At the very least, he could have said 1. Get a prayer shawl. 2. Get a shofar. 3. Get out of Egypt. Discussing these steps would have been a good follow up. Again, perhaps a future book has this in mind, but the war is now, not later. Steps taken to fight after main battles are over are of no use. If the purpose is color commentary and a rallying to pray, okay. Make the book shorter and say that in the first twenty pages, and move on. That is, after all, a part of how these “gods” are defeated.

ISBN: 978-0143130062

ISBN: 978-0143130062

Here is how a conversation might have happened with the publisher and the author of this book, Winifred Gallagher:

Publisher: So we are looking for a top-notch academically researched piece on the United States Post Office and what you have submitted here looks good!

Author: Awesome!

Publisher: Just one thing though, we are gonna need you to cover the history of Black Americans in the US Postal service, and make sure to talk also about women.

Author: Er..kay?

Publisher: Look, in 2016 liberal bookstores and publishers want to hear about Black Americans and women because they are the oppressed despite Women’s Lib, and despite the Civil War.

Author: Well…okay…I think I can make that happen…

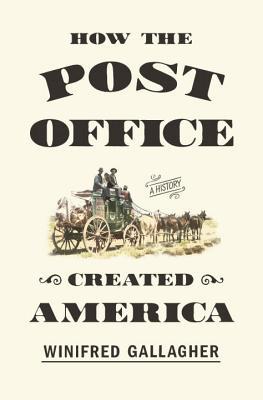

The short outcome, of that hypothetical conversation, is that Gallagher did do that, but she did it in such a way that it is distracting. There are easily three other books within this book, and the identity crisis shows. The two other books should respectively be African Americans in the US Postal System, and Women and Their Role In the US Postal System. Or, it might have been better to divide the subject into the US Postal System previous to 1940 and then 1940 going forward. Why? Because this book, while offering a lot of awesome history, seeks to beat you across the face with the other two works when the narrative format does not support these excursions. There are moments where it does–where Postmasters are being discussed broadly and the discussion of the first woman Postmaster makes perfect sense. There are other times where it is more like, “So now we are going to talk about women because we must.” The change in focus is forced and unjustified. It makes the reading choppy and disconnected.

On the other hand, this book does an excellent job of showing how the early US Postal system was the glue that held the nation together when it came to educating citizens on the events of the day. There were those like Benjamin Franklin who figured out how to game the system and use their free franking privileges to make themselves wealthier. Of course, he also helped significantly improve the delivery of the mail by offering refinements to the postal system at large.

From these early origins we are ushered into the pre-Civil War US Postal System which is rough and tumble. Roads are in poor shape, and the job is dangerous in ways that directly imperil a person’s life–whether that be through Native American attacks–or natural phenomena like rivers that are flooding or hard to cross. Oh yeah, there are also thieves on the journey, who like stealing mail because there might be something worth stealing since the mail is the main way things are sent–like money or even later the Hope Diamond. This is where the Pony Express exists, and it was, indeed, a dangerous job that advertised that it preferred orphans who would not be missed should they not make it back home. Far from deterring applicants, it seemed to embolden them.

At the point we find ourselves in the company of Andrew Jackson, we begin to understand something about the spoils system and how politics began to interleave itself into the mail system via governmental appointments which typically paid well and had the perk of retirement–especially as the system became more modern.

As we move forward into the Civil War, we find another gutting by Lincoln of the US Postal Service which, more or less, removed many people who had held on from the time of Jackson. In the meantime, trains are beginning to become a dominant force for faster delivery of mail, and are starting to replace the horse. Of course, there are not trains available everywhere, so the horse delivery system must be kept for those areas that lack any other kind of means of delivery. The trains begin to act more like private carriers, and in addition to their efforts to make money as kinds of postal businesses, there are other places who, like the Pony Express, try to discover an angle to either make money doing private deliveries with priority, or to be awarded contracts by the US government by becoming a part of the US Postal system.

As things start to head into the 1900’s, we start seeing the effects of the Industrial Revolution and the turn toward mechanization. The Postal Service becomes behind the times due to infighting in the government about who can deliver what, and when. Everyone is after the money aspect of the situation, and no one wants to fund changes that are necessary to keep the system functional for contemporary usage. Everyone is depending, however, on the mail to run. Pulp kinds of books and magazines have specific rates that the publishers do not want to see change. Some of these are political newspapers, and some, according to the book, are little better than smut.

Eventually we are aloft in the air and we are introduced to the pilots who risk the early dangers of aviation that perform feats that would still be risky today with modern planes. We find ourselves, by the Great Depression, surrounded by some barnstormer pilots, and a postal system on the brink of collapse which causes New Deal economic forces to start construction programs on Post Office buildings. Fixing the Post Office up as a kind of cultural heritage of a region becomes the new reinvigoration though there still are massive problems with regard to labor forces and how the government can deal with a system that must run and yet is being simultaneously crippled.

It is around this juncture that another hypothetical conversation must have happened:

Publisher: You really, really need to focus on MORE women and MORE Black Americans! Turn the knob up from about a 3 to something like a 7!

Author: Okay, I think I can do that!

The author yanks off the knob and cranks the effort up to a 12, fearing the publishing contract will be nullified if the black/woman quota is not met.

So, naturally, there are many more references to black men and women in general in the more modern US Postal Service. At this point, a time-traveler arrives from the year 2025 and shakes the author by the shoulders and utters one word and only one word: FATIGUE!

The rest of the book, on a less flippant note, takes us right on up to the 60’s and 70’s where mail stops being delivered and Postal Workers begin to strike because they have had enough. Nixon, we discover, adopts the eagle as the US Postal logo in part because the horse used before as the symbol was hard to recognize. We learn about a system introduced in the 40’s that goes extinct in the 60’s which is a successful parallel US banking system which is run through the Post Office. Also, mechanization begins to assert an ever-increasingly more powerful grip on how the mail is run.

We take some forays into stamps and their value, and how collectors can get mad when the government does not let them purchase stamps they think will be valuable. We learn also, that releasing stamps of events is kind-of-a-big-deal and if it they commemorate someone in the modern time, it is usually the case they are dead since if they are still alive they can screw up their reputation in a way that reflects negatively on the Post Office.

What shines throughout the work, and invites comparison, is how the development of the internet mirrors closely that of the US Post Office. From centralized hubs, to the eventual hub and spoke systems, every kind of network architecture is discussed with regard to the postal system. The book concludes with the statement that the US Postal System failed to see the impact that the internet would have on mail and the US Postal System in general, and that failure was not for want of Postmasters who understood what was going to happen. Though the book does not say it, it is probably the case that many understood the problem, but who wanted to again assume the cost of changing the postal system? While the amount of letters may have dropped, the text notes that the increase in packages from shopping is sharply up. It turns out that to get goods from digital shopping, you still need someone to saddle up their horse, and actually take the package to the customer. Who knew?

It is toward the end of this book that I suspect the new book idea emerges as a conversation between author and publisher:

Publisher: All right, you got plenty of black people in there, and great job on the women. It reads smooth as butter. We need you to release a new book though. What we are thinking, and we are just spit-balling here, is that maybe you can cover the gay-trans-vampire contribution to the US Postal System. That, and people who identify as furries. Can you work that into a narrative on the history of the US Postal Service?

Author: Well, that is going to be difficult, but I suppose I could just always transition with the subtext of “Furries who never failed,” or “How Edward glittered his way into my mailbox even though I don’t know what pronouns to use.”

Publisher: Great, GREAT! I’m looking forward to it! Send it along when you work it up!

Rest assured, if this happens, thebooklight will review the copy, mercilessly.

ISBN:9781770894303

ISBN:9781770894303 ISBN: 978-0143130062

ISBN: 978-0143130062