978-1959666455

978-1959666455

Special thanks to https://wisepathbooks.com/ for supplying a review copy of this book. –Booklight staff

“Old Grog”, the author of On Ruling, has undertaken a difficult task against the current political climate. He has attempted to weave a helpful narrative toward Christian men that acts as a beacon concerning masculinity and what it ought to look like under a relationship with the acceptance of Messiah as the cornerstone. In many ways, he has succeeded in this.

The book hopes to supplant any future books about Christian male leadership and notes, wryly, that most men that have many books on Christian leadership seem to be the worst at exhibiting it. There is a tongue-in-cheek method of relational tale-bearing that works concerning the tone of the thesis. Since the intended audience is mostly young men, this device is well-suited toward that goal.

The focal point of the exposition is the induction of men into a status that is referred to as a “viceroy”. A viceroy is defined, loosely for the purposes of this review, as an appointed ruler under a king to carry out certain duties necessary to the functioning of the kingdom. The King is then wisely referred to as the Messiah. This neatly sidesteps the problems inherent when believers think of themselves as Kings in the manner of Israel or lost tribes, but not as examples like David. Even with this language, though, there is a reminder that a ruler ought to be humble first and foremost in case anyone who begins to carry out the viceroy mentality begins to inflate their self-worth in a manner that might incur the wrath of the King of Kings.

Nonetheless, the comparison to what Kings do oftentimes makes the distinction fuzzy. While the work makes the concept of Kings in general a natural thing, sometimes Kings from the past are used as a reference point. (or at the very least, that is the inference) This has the unintended effect, possibly, of making the viceroy step into the shoes of a King, whether or not the author is intending for the viceroy to do so. This becomes highly important later when the reader is told about the behaviors Kings might exhibit–such as showing up unannounced and gathering resources and making alliances. These suggestions are made in terms of enlarging the dominion of God on the Earth, but for young men, as anyone can tell you, sometimes the nuance is lost.

Predictably, the book leans heavily toward what the behavior ought to be for the home, the wife, and having children. There are some hard-won pieces of advice present here. Certainly, the characteristic of having worked long in the business culture is evident. Generally speaking, it is probably good advice, although some of the examples used about vaccinations and being a pharmaceutical sales person are puzzling. What happens, for instance, when the King of Kings says that certain businesses, like the types mentioned in the book, are not working for Him?

Furthermore, the guidance the Messiah gave was to sell all possessions and follow Him in most circumstances and to share all possessions in common among the disciples. The model in this book does not incorporate that specific teaching which is a crucial one to understand properly.

There is an acknowledgement, obliquely, which underlies why this point bears emphasizing. The reader is told that fifty years ago a book like On Ruling would not need to exist since there was a common agreement on what a masculine role ought to be. The trouble, though, is that role is under assault because some of the lessons in this book were put into practice and not always under the Will of God. In the language of the book, “A whole lot of hay was cut”, but the collective values were wrong. Many viceroys were mistaken.

A guiding lesson is given concerning how these values were corrupt enough to warrant this book’s existence. A young man who comes from a home where he has “two mothers” impregnates a girl in college. He is, of course, fearful, but his problem is what this book is trying to address–namely that he has no idea what a Father is because he never had one. An immediate lesson is offered to this young man in the form of responsibility for his new family, consequences, and new priorities.

A most interesting part concerns the criticism that the advice given might turn the home and family into an idol since that is the clear priority throughout the reading. The author takes a kind of “the ends justify the means” outlook here in that the children produced from this implemented strategy will more than make up for any suspicion that the home is an idol. Whether or not this succeeds as an argument depends on whether a person agrees that the children ought to be emphasized in the way this book purports.

The biggest visible stumbling block in the arguments expounded concerns the choice of the word “Kings” and the monarch allusions. In the end of days, there comes a personage, it is told, who comes in the guise of a King. Many young men, it seems to the reader, do not have a problem with being royals. What they have trouble with, though, is submission of their “royal impulses” to the Higher Will–and certainly the consequences that come when that fails to happen appropriately. The biggest ill concerns the quality of restraint more so than the characteristic of regal identity. Of course, “Old Grog” might be seeing an angle the reviewer is missing. Sometimes one has to “build up” before one can “tear down”.

On the other hand, it is also told that Israel is eventually to become a nation of Priest-Kings. “Old Grog” does not take this stance, but rather emphasizes the more Pauline position that he is speaking as a kind of “grafted-in” pagan which many Christians likely relate to. Perhaps this work is framed from that vantage point, although if it is, it did not seem to state that point plainly enough as to make an impression on the memory after reading it.

As a composite, the work is an interesting read with a lot of life advice from the aspect of a young man who is going to start a family and will be out in the working world. On the other hand, depending on how close the Kingdom is to arrival, this might be unnecessary advice. The world is changing faster than most people can keep a fix on. The nature of work and how faith is arranged in society has changed drastically in the last five years. Still, the qualities “Old Grog” puts forth will be important, regardless of the backdrop in which they exist. The work undertaken here is pertinent for men of faith to read, and men in general can derive value from considering the ideas put forth.

If you are a young man, this book will make you think about what you want to do. If you are of middle age, it will make you think about what you are doing. If you are an older man the book makes you consider the kind of advice you would give to men younger than you in light of your life and spiritual growth. Wherever it is you are or were, it will make you think about the definition of what it means to be male and what expressions that ought to take with submission to Messiah as an intrinsic emphasis.

978-0465030095

978-0465030095

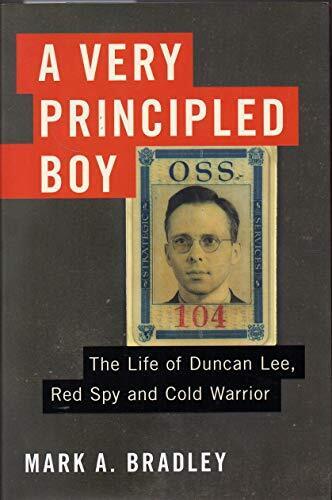

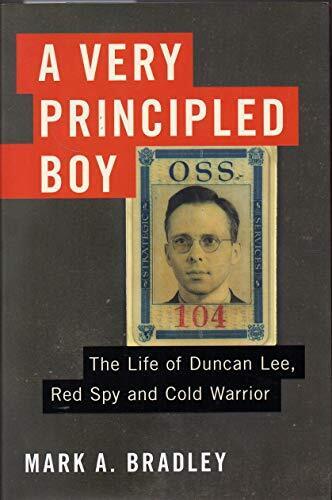

Mark Bradley decided to take on a difficult task. The story of Duncan Lee is not one that most authors would want to tackle, since the subject of the work could be easily characterized as an unrepentant traitor for communist Russia under Stalin.

Lee would dispute this, and so would Lee’s family. Probably, the rationale Lee would offer, as per the framework of the book, was that the goal was to defeat Hitler at any cost. Lee saw Stalin and Russia as key to this. This, however, of course overlooks the fact that Lee was a communist because he liked the ideology of communism.

The way Bradley tells the narrative makes chronological sense. The basic divisions are the early life of Lee, pre-war, the college life of Lee, where he begins his communist journey, the war life of Lee, where he becomes an OSS officer but also a supplier of information to Russia, and the fallout later life of Lee, where the consequences under McCarthy begin to corner Lee.

The most interesting part of the story concerns how Lee deceived himself. He starts off clearly as a Russian spy, but then later after the charges begin to be made concerning his activities, he reverses his role and goes to China to support an airline industry with strong opponents of communism. His job, with this specific airline, is to resist the advancing Mao in China.

So, the question becomes who, exactly, is Duncan Lee? His family had been in America for some time, and was related to Robert E. Lee. His immediate family, in the form of his father, was an evangelical who went to China to witness for the gospel there. Bradley juxtaposes this action against Lee who inherits this spiritual zeal, but uses it for the “religious” purposes of communism and advancing its goals.

Being part of the intellectual class, Lee heads off to Oxford and finds a future wife there who is more radical for communism than Lee. This serves to galvanize his early devotion.

Later, during the war, the emergent OSS under Donovan taps on Lee to hold an important position inside the organization. Since Lee has been rubbing shoulders with members of CPUSA–the Communist Party of the USA–it does not take long for Russian intelligence to find a suitable handler for him in the form of Mary Price who believes spying for Russia is a form of fighting fascism. The way she recruits Lee is possibly one of the oldest in the book–through sexual seduction in part. Lee refuses to give Price any written information, however, and makes her memorize what he has to say so that there is no paper trail. This proves to be a later boon to Lee.

Lee is not a very good spy for Russia since he refuses to do what they want him to do and he continues to do things his own way. He also does not have the required emotional stamina, and soon begins to have a kind of fearful paranoia run his life. Since his treachery level was so high, one concludes this is probably Lee’s guilty conscience more than any external threat, although the two do blend together on several occasions.

Once Russia aligns as an ally of the US, Stalin uses the new scenario to his advantage since he knows the US does not want to try any specific Soviet spies it might find in its ranks due to upsetting Russia and having a situation unfold whereby Russia might withhold some of its manpower from the war effort. It is, ironically, at this point, that Lee begins to become more paranoid since two sides which were not originally speaking to one another begin to have more communication and understanding of who is supporting whom in the spy world.

When the war finally ends, Lee, through the machinations of the person who replaces Mary Price, an Elizabeth Bentley, faces whistle-blowing charges. Bentley begins to not like the direction communism is taking for a variety of reasons, and for her own protection from Russia decides to venture to the FBI and unmask her network of Russian spies. The FBI of course, does not initially trust or believe her fully, but it puts enough pressure on Lee to make him wary. It is not long after this that he is off to China to assist the airline that the CIA saves which is called CAT in its pro Chiang Kai-shek activities which includes supplying his army and ultimately his ex-filtration to Taiwan. This provides Lee an entirely different narrative, which he uses in the coming trials which are in part a result from Bentley’s admissions–performed by the House Un-American Committee.

Eventually, Lee is off to Bermuda for his new job with an insurance company, where he faces more trouble in the form of gaining necessary passports and being summoned back to the US to face further questioning because of Bentley.

Here, the narrative plays out to its ultimate conclusion of Lee as an older man, and what he, in his own opinion, thinks about his life. Of course, true to the form of everything else Lee has done in his life, his conclusions are myopic and flawed. The reader is in the best position to make the judgment.

Bradley tries to play this story down the center and uses phraseology that condemns communism at times, and patriotism at other times. He does mention, by the end of the book, that he is a former CIA employee and that the CIA had to read all the material and approve it. Perhaps this plays into the case of Duncan Lee, and perhaps not. Perhaps Bradley, like Lee, felt a need to atone for something, and so wrote this book and worked with the Lee family to produce it. None of this sounds like an easy or delightful task. The story, for whatever reason, had to be told.

The question, like the life of Duncan Lee, is why?

978-0300270198

978-0300270198

Review note: Special thanks to Yale University Press for providing an electronic review copy of this work –Booklight staff

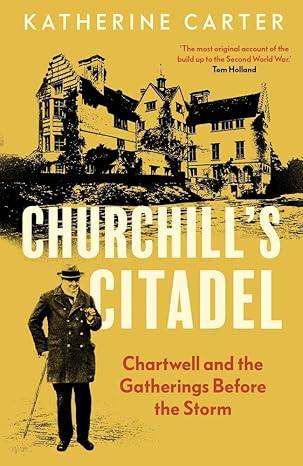

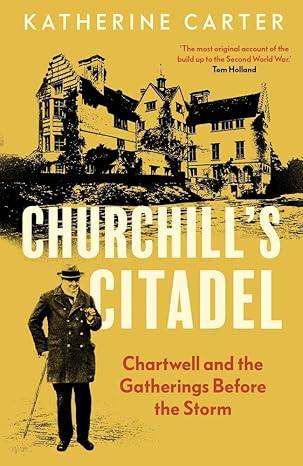

Katherine Carter has spent, according to this work, ten years at Chartwell which is a long time to research and explore. To an American ear, this might not set off immediate connection since Chartwell is a subject that has flown below the radar concerning World War II. The needed reference point concerns the knowledge that Chartwell was Winston Churchill’s country abode. What makes Chartwell interesting, however, is that it also served as a place where Churchill amassed military intelligence from many sources from well before Hitler came fully into power. Chartwell, then, was where secret meetings with people such as Einstein and China’s political elite took place. It is also where people such as the famed ‘T.E. Lawrence’–better known as Lawrence of Arabia–met Churchill before Lawrence’s untimely, unfortunately fatal, motorcycle wreck.

What the narrative endeavors to undertake is how and in what way Chartwell influenced the development of Churchill’s political career. A strong metaphor can be made to Chartwell being Churchill’s Garden of Eden. This metaphor is helped, perhaps in not a small way, by key political players in Churchill’s retinue being named Eden.

Here, at Chartwell, Churchill banged out various writing pieces and crafted speeches designed to warn the world of the approaching Nazi menace to which it turned, until the situation became dire, a deaf ear. Principally, Churchill wished to ready the Air Force so that Britain could counter any attack that Germany might be inclined to send. An early partner in this endeavor, who is an interesting study all on his own, is a person by the name of Ralph Wigram who acts as a key informant to Churchill on Germany’s rearmament. It may be the Wigram was a pivotal piece that was necessary so that Churchill could forge his own convictions about the coming world conflagration. If nothing else, he was an important informant that helped shape Churchill’s opinion in 1934.

Here at Chartwell also was where Churchill banqueted with especially formal meals and recipes for as long as his budget could afford to do so. Eventually, however, pecuniary necessity begins to settle on the estate, and Churchill must wrestle with what to do with the place that he so dearly loves. The decision he makes proves to be fodder for a later scandal.

Carter includes details that are not easily discovered concerning the early parts of World War II, or to borrow a famous Watergate phrase, “What Churchill knew and when he knew it.” It paints a picture of Joseph Kennedy and an America that is not especially fond of Britain, nor desirous of entering into any further conflicts. Likewise, it shows a Britain that wishes to close its eyes to the menace soon to be at its borders and wishes instead to avoid any direct action that might lead to more conflict. Chamberlain, famously, wanted ‘peace at any price’ and this appeasement, of course, was desired from having witnessed the horrors of the First World War. Carter also tells the narratives of deposed French Prime Ministers, ousted Nazi political opponents of former high station, and German military informants who cannot believe that Hitler is doing in Germany what he appears to be doing.

Oh yes, and there there is the all-encompassing story of Churchill’s ambition to politically ‘get back on top’. His reasoning for desiring these political positions are ultimately good in context, but it is clear he wants to be back where he was–somewhere in Admiralty. His course would take him to the office of Prime Minister. Carter’s exploration of how Chartwell contributes to this trajectory is novel.

A piece of criticism of Carter’s work, however, might be that the ending is unexpectedly abrupt. One feels, somehow, like there is more to be said about Chartwell at the end of the war. This is especially so since we learn all about Churchill’s family and what they do there and we do not get to hear what happens once the dark cloud of war passes from Chartwell’s perspective. What we do get, which is quite nice, is a long timeline of events after what feels like an abrupt ending–and a detailed number of notes and sources. Perhaps Carter plans a sequel to this work some day. If so, the ending makes sense. Churchill himself, assuredly, would approve.

978-1959666455

978-1959666455 978-0465030095

978-0465030095 978-0300270198

978-0300270198