0-449-00561-5

0-449-00561-5

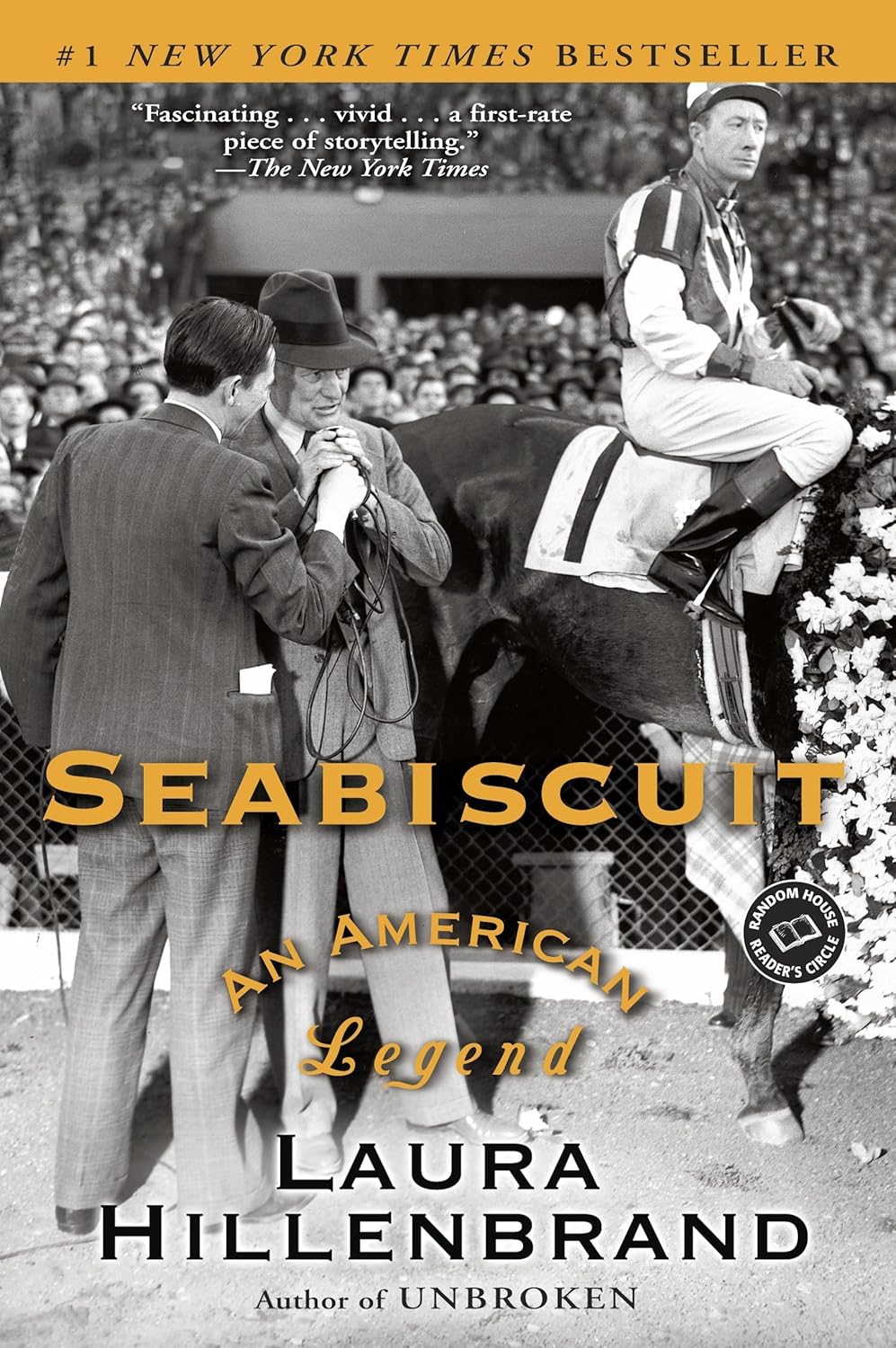

Review note: One of the staff members in the earlier days of Facebook had Hillenbrand as a friend. Seabiscuit was out then. –Booklight staff

In case you ever want to know how long it takes books to get that weathered yellowing that books of antiquity often characteristically possess, the answer is about 25 years it seems, since the review copy of this work looked like it might have been around as a witness to the races of Seabiscuit during his prime.

Hillenbrand has a nose for stories. Her previous work, Unbroken, was reviewed by this site. Seabiscuit as a narrative theme, echoes some of what Unbroken encapsulated. The idea of the unlikely or unknown coming into a position of world notice only to encounter some insurmountable-seeming obstacle is something that both works share as the subjects of both books had to face uncommon amounts of hardship.

What makes Seabiscuit captivating though, is not necessarily the writing, though it is good, but the story itself. Hillenbrand is able to weave the narrative structure together such that the reader is transported back to the early 30’s when Seabiscuit was starting his ascent into national domination of horse racing.

Some of “The Biscuit’s” retinue is well known since the tale is frequently crossing paths with the likes of Bing Crosby who is surrounded by the kind of people one would expect for his time and place.

If you have ever wondered what the profession of a horse jockey is like, Seabiscuit is an eye-opening encounter of the hardships and dangers incumbent on those who pursued the sport and profession. In short, the conditions were barely above awful, and it is a wonder that any jockey stuck around through those years and even now since the same dangers are present.

What one learns, however, is that the jockeys are riding for freedom–or a kind of transcendence that only horse racing provides and arguably only Seabiscut could uniquely channel such than the entire US paid attention to his races above concerns even of a burgeoning World War II. We learn in the book that FDR kept diplomats waiting just to hear whether or not Seabiscuit would win a certain race against another horse that is still well-known who went by the name of War Admiral.

There is a kind of chaos that sets up around the races and the characters in them–and it is not a unique occurrence since it seems to happen in almost each race. Sometimes it happens during the race, and this usually portends a jockey either being seriously hurt or dead.

Seabiscuit seems, at one point or another, to trick everyone or to play tricks on everyone. The beginning narrative deals with Tom Smith, an enigmatic cowboy type, coming into the ranch and discovering what Seabiscuit’s psychology is after having discovered him. At the same time “Red” Pollard, Seabiscuit’s first real jockey, starts to comprehend what it means to motivate Seabiscuit to win. The fact that Seabiscuit requires motivation is an interesting spin, since most horses naturally seem to run, but Seabiscuit is not a “natural horse” as the story shows.

Pollard acts, at first, as Seabiscuit’s savior, and then later Seabiscuit acts more as his. The two of them are intertangled, and although Seabiscuit is ridden by another jockey for a time by the name of Wolf, eventually everything comes back to Pollard at a crucial moment for both jockey and horse.

We also learn about Charles S. Howard, the owner of Seabiscuit, who also kicks car ownership into existence with the early sales of Buicks in California assisted, in a major way, by the California earthquake of 1906.The Quake, we learn, made horses sparse, and cars were, on the contrary, plentiful. (so long as you bought them from Charles S. Howard’s lot) Howard, paradoxically, gets into horse racing, which is the animal he is replacing with the newest technology.

The pacing of Seabiscuit is fast, but it never becomes tedious. The story is worth at least one reading, and probably several additional ones as a kind of reminder about adversity and what can be done when the world arrays itself against you–maybe especially the media, gossip, and slander. (and your competition) Seabiscuit overcame it all, and became a legend. So too did the people who managed him. Somewhere in there though, a large portion of faith was involved, because in many given instances, things looked bad at best and hopeless at worst. Know anyone who can use some inspiration?

ISBN 0-394-54618-0

ISBN 0-394-54618-0

The expectations for Yiddish Folktales by Wolf and Weinreich require some adjusting. If you believe you will be reading about Elijah against various mythical backdrops, you will be right. On the other hand, if you are not expecting elves, ghosts, witches, and sorcerers, you will not be prepared for what you will find in the pages.

These tales are culled from people who were Yiddish from around the 1910’s and 1920’s. Many of them are Russian in origin. There are also smatterings of stories that have distinctly Germanic origins. Between all of them exists a type of story-telling that is as rich as any other culture when it comes to creatures that are relegated to the fantasy genre in the modern era of reading.

Some historical figures are present too whose influence and exertion of will is still felt during the storytelling time in which this book was composed and based. Tsar Nicholas the First shows up sometimes for the better, and sometimes for the worse. Napoleon also obtains some billing although it seems that many of his tales are cautionary.

There are several accounts that are classed as “Purim Tales” in that they court nonsense or have no ending that makes logical sense. Many of these stories are acknowledged as being these kinds of yarns by a certain kind of Yiddish rhyme that indicates somebody was drinking alcohol, but not the storyteller. (The teller of stories is, after all, the arbiter of truth)

In addition to many of these oral traditions, there are explanations as to how the storytelling was done, and what the climate was like around people who told tales. The primary source of entertainment during the early 20th and late 19th centuries were people who could tell stories and they had an elevated position among their social strata because people wanted to hear what they had to relate. Often, the storyteller appears near a stove, probably because many of these events happened more often when it was cold than when the weather was warm and people would be more active outside.

Satan shows up more frequently than perhaps he ought to, but usually he only makes an appearance to remind the listener that Satan is constantly pulling some manner of tricky trick. There are also prods that one ought to develop their character instead of their bank account, and that sometimes people who are foolish seeming are not inferior to those who are considered smart or wise. (indeed, they often get the better of the deal since being foolish they have no reason to use their intellect in malignant ways)

If there is a latent desire to understand what Yiddish culture developed, this book is an excellent work to give the reader insight into the oral story traditions it commanded. Be prepared, however, to understand the world not through the stereotypical Hebrew lens, but more like Lord of the Rings and the Hebrew Bible had some strange offspring. By the time you are done, you will probably wonder why these traditions have so few cinematic representations, whereas other cultures and their folktales have so many as to be nearly synonymous with some of these accounts. It isn’t appropriation, after all, when you have spent hundreds of years in a place and developed your own unique experiences with entities that show up in other traditions. By that point, it is the lens your culture uses to parse experiences in those places with its own unique fingerprints. Weinreich and Wolf are as good of a place as any to begin that exploration.

ISBN: 1718873980

ISBN: 1718873980

Special thanks to https://wisepathbooks.com/ for supplying a review copy of this book. –Booklight staff

There are not too many books that straddle the line between Christianity and mysticism that are able to negotiate the twists and turns the subject matter entails well. George MacDonald took an early swipe at the future genre in 1881 with this work.

It proves hard to categorize what the author did. There are plenty of allusions and symbolic meanings present in the volume. The quick storyline is that a young man inherits an estate that is on the verge of ruin in Scotland. This is far too simple of a reduction, however, of the rich layers present in this work.

Probably, it would be better to say that a young man learns what it means to mature into an adult spiritually while keeping the Christian teachings close at hand, as well as making sure the soul does not slip from him while balancing the demands placed upon him by the world.

The estate he is to inherit is curious and is not without its ghosts. The walls of the house speak of the ancient history of his family, but indeed also of his mother who the reader learns, has died earlier in his life. His father is a constant reminder of what it means to be noble and to stay meek. The other characters in the house help to tell Cosmo, the boy, about his past, and have key pieces of information about his future.

It is via a chance bad weather meeting that Cosmo meets Joan who is entangled with his life in several key ways and he in hers. While their initial meeting seems to have something romantic about it, there are other possibilities closer at home, and a large portion of the novel concerns itself with how the two reconcile their incipient feelings for one another.

There are, of course, massive doses of supernatural happenings throughout the work. The bulk of these could be summarized by saying God turns what seems to be meant toward misfortune toward good where the Warlock estate is concerned.

It is also curious that the book was named Castle Warlock with the obvious connotations that entails considering that the narrative of the book is very much how to be a good Christian. It is said by some sources that C.S. Lewis used this work to construct some of his other more famous novels. Indeed, there is the courting with the magical smacked up against the Christian as one often finds in his novels. While the two themes move fluidly enough between one another in a Scottish castle, it would require a place like Narnia for Lewis to make the confluence happen.

One difficulty in accessing this work is that the accents are authentic to Scotland. Indeed, there even exist alternative language versions written in Highland kinds of tongues or Scots-English. After awhile, it becomes easier to understand what is being said as the reader begins to develop the vocabulary meanings through context and repetition. Still, there are some key moments where the reader might not have everything said easily understood and these moments require a later clarification when they contain key pieces of plot.

This kind of work is not a modern undertaking in any sense of the word since the entirety of the story exists as a kind of parable as well as a tale. Still, there is a richness accessible to the determined reader that most modern literature cannot replicate. One could do worse than spend several evenings by the reading light decoding some Scottish turns-of-phrase.

0-449-00561-5

0-449-00561-5 ISBN 0-394-54618-0

ISBN 0-394-54618-0 ISBN: 1718873980

ISBN: 1718873980